Tether in 2025: a Capital Analysis

When I graduated and applied for my first job in management consulting, I did what most ambitious yet spineless male graduates used to do: I chose the one firm that worked exclusively with financial institutions. In 2006, banks were cool. They also tended to occupy the grandest buildings in the prettiest neighborhoods of Western Europe, and at the time I wanted to travel. What nobody told me was that the package came wrapped to another, far more serpentine clause: I would be married, indefinitely, to one of the largest yet most specialized industries on the planet. Demand for banking specialists never goes away. When the economy expands, banks get creative and need capital. When it contracts, banks need to restructure and (again) need capital. I tried to escape the vortex; like any codependent relationship, it was harder than it looked.

The public often assumes that bankers understand banking. A reasonable assumption, but wrong. Bankers organize themselves into sector and product silos. A telecom banker knows far more about telcos (and their financing quirks) than about banking itself. Those who devote their careers to serving banks (the bankers’ bankers, the FIG crowd) are a peculiar breed. And universally despised. They are the losers among losers. Every investment banker dreams, in between the midnight spreadsheet revisions, of escaping to private equity or the startup world. But not FIG bankers. Their fate is sealed. Condemned to golden servitude, they inhabit an industry folded in on itself, largely ignored by everyone else. Banking for banks is deeply philosophical, occasionally beautiful, but mostly invisible. Until DeFi came along.

DeFi made lending and borrowing fashionable, and suddenly every fintech marketing savant felt entitled to comment on subjects they barely recognized. And so the dusty discipline of hardcore banking-for-banks resurfaced. If you arrive in DeFi, or crypto, carrying a suitcase full of brilliant ideas about rewiring finance and understanding balance sheets, just know that somewhere in Canary Wharf, Wall Street, or Basel, a nameless FIG analyst probably thought of it twenty years ago.

I too was a miserable bankers’ banker. And this is my revenge.

Tether: Schrödinger’s Stablecoin

Two and a half years have passed since I last wrote about crypto’s favorite mystery: Tether’s balance sheet.

Few things have captured practitioners’ imagination quite like the composition of $USDT’s financial reserves. Most commentary, however, still revolves around whether Tether is solvent or broke, lacking the required framework making the debate useful. While the concept of solvency has a clear meaning for traditional corporates that must at least match liabilities with assets, the concept begins to wobble when applied to financial institutions, where cash flows fade into the background and solvency is better understood as the relationship between the amount of risk a balance sheet is carrying in its belly and the outstanding liabilities owed to depositors and other financing providers. In financial institutions, solvency is a statistical notion rather than an arithmetic one. If this sounds counterintuitive don’t worry; bank accounting and balance sheet analysis have always been among the most specialized corners of finance—it’s amusing and depressing to watch people improvise their own frameworks for judging solvency.

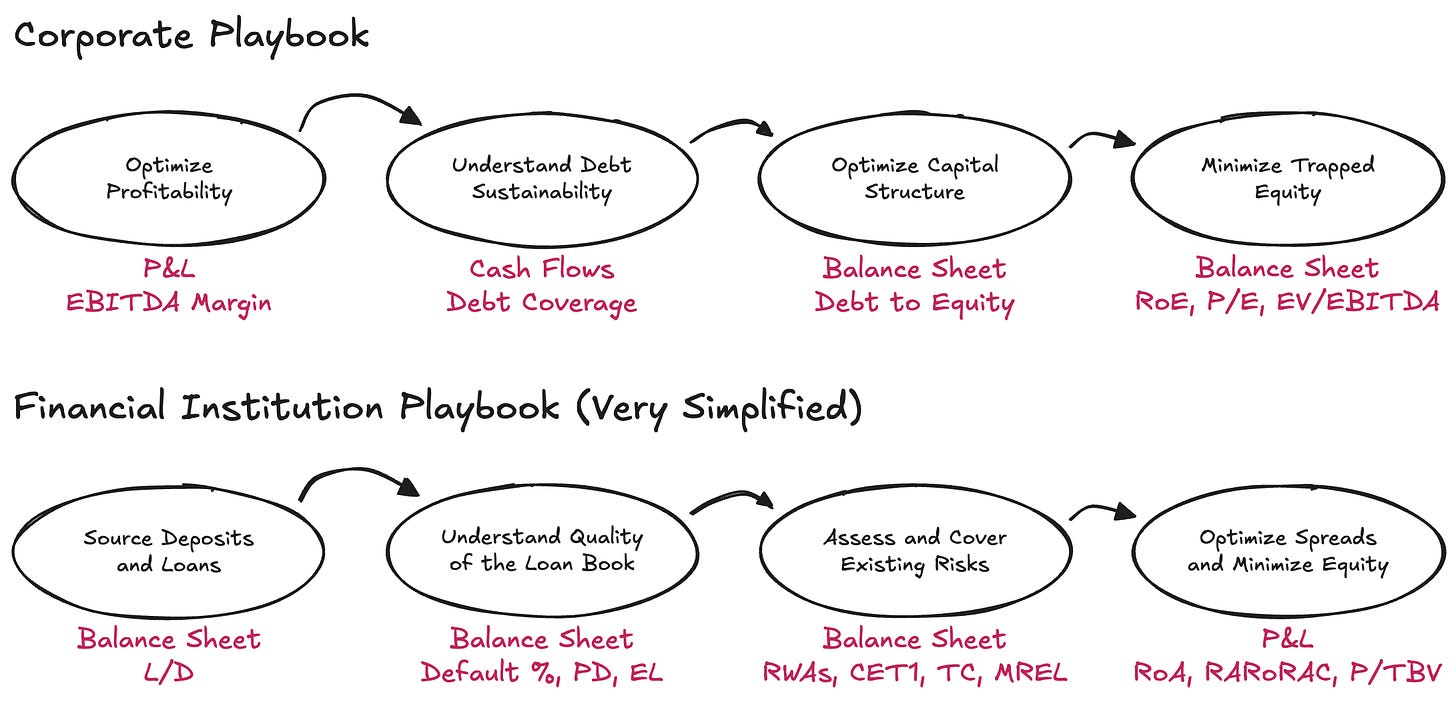

Effectively, understanding financial institutions requires flipping the corporate logic on its head. Rather than starting from the P&L, you start from the balance sheet—and ignore cash flows. And debt, far from being a constraint, is the raw material of the business. What matters is how assets and liabilities are arranged, whether there is enough capital for rainy days, and whether there is enough return left for those capital providers.

The Tether topic resurfaced after a recent S&P note—a report so thin and mechanical that it was its traction, rather than anything else, the most interesting part of the story. At the end of Q1 2025 Tether had issued c. $174.5b of digital tokens, mostly USD-pegged stablecoins and a bit of digital gold. Those coins give a 1-for-1 redemption claim to qualified holders. In order to back those claims, Tether International, S.A. de C.V. held c. $181.2b of assets—in other words holding excess reserves for c. $6.8b. Is this net asset figure good enough? To answer that (without inventing yet another bespoke framework) we need to ask a more basic question: which existing framework should apply in the first place? And to choose the right framework, we must start with the most fundamental observation of all: what business is Tether actually in?

A Day in a Bank’s Life

Tether’s business is, at its core, the issuance of on-demand digital deposit instruments that circulate freely across crypto markets, and the investment of those liabilities into a diversified pool of assets. I use investing liabilities rather than holding reserves deliberately: rather than executing same-risk / same-duration custody of those funds, Tether actively opines on asset allocation and earns the spread between the yield on its assets and the (near-zero) cost of its liabilities, operating under only loosely defined guidelines on how those assets should be deployed.

In this respect, Tether looks far more like a bank than a money transmitter—an unregulated bank, to be precise. Banks, in the simplest framing, are required to hold a minimum amount of economic capital (I am using capital and net assets interchangeably here—my FIG-friends will forgive me) to absorb both expected and unexpected volatility in their asset portfolios, plus some other things. This requirement exists for a reason: banks enjoy a state-granted monopoly over the safeguarding of household and corporate funds, and that privilege demands a corresponding buffer against the risks embedded in their own balance sheets.

When it comes to banks, regulators are particularly opinionated on three things:

- The types of risks a bank must account for

- The nature of what qualifies as capital

- The amount of that capital a bank must hold

Types of Risk → Regulators codify the various risks that can erode the redeemable value of a bank’s assets when those assets are ultimately called upon to meet its liabilities:

- Credit risk. The possibility that a borrower will not fully meet its obligations when required—this type of risks accounts for 80-90% of risk-weighted assets for most G-SIBs

- Market risk. The risk that the value of an asset (even in the absence of credit or counterparty deterioration) moves unfavorably relative to the denomination of the liabilities. This is what happens when depositors expect e.g. USD but the institution has decided to hold gold of $BTC. Also, interest-rate risk sits within this category. This type of risks accounts for 2-5% of risk-weighted assets

- Operational risk. The ambient risk of running a business: fraud, system failures, legal losses, and the broad universe of internal mishaps that can impair a balance sheet. This type of risks is residual on RWAs

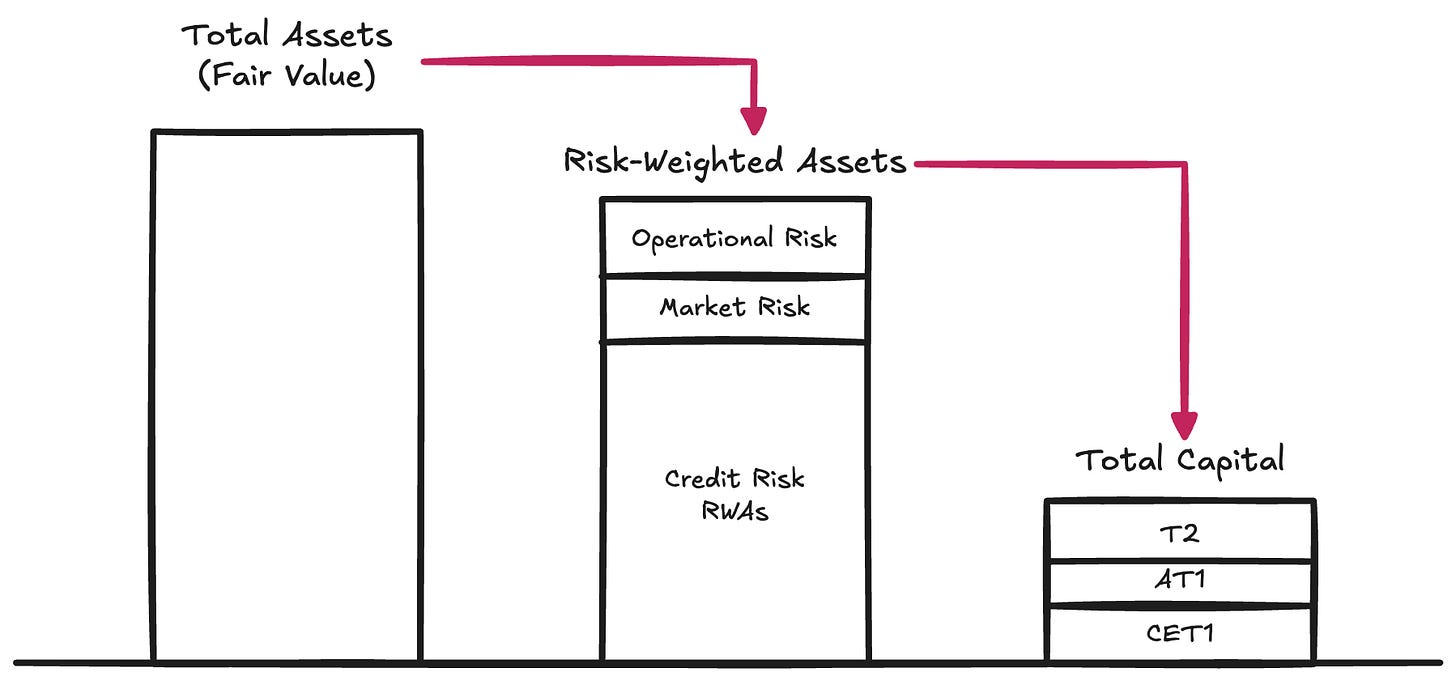

These requirements form Pillar I of the Basel Capital framework—still the dominant system for defining prudential capital in regulated institutions. Capital is the raw material required to ensure that their balance sheet contains enough value to meet redemptions (within a typical pace—read liquidity risk) from liability holders.

Nature of Capital → Equity is expensive—as the most junior form of capital it is indeed the most expensive form of financing a business can get. Over the years, banks learned to become extremely creative in reducing the amount and cost of the equity they require. This led to the emergence of a long catalogue of so-called hybrid instruments—securities engineered to behave economically somehow like debt, yet designed to tick the regulatory boxes required to be treated as equity capital. Examples include perpetual subordinated notes, which have no maturity and can absorb losses; contingent convertible bonds—CoCos, which automatically convert into equity when capital falls below a trigger; and Additional Tier 1 instruments, which can be written down entirely in stress scenarios, as we saw most vividly in the Credit Suisse resolution. Because of this proliferation, regulators distinguish between different qualities of capital. Common Equity Tier 1 sits at the top: the purest, most loss-absorbing form of economic capital. Below it, progressively less pristine instruments fill out the stack.

For our purposes, however, we can abstract away from these internal distinctions and focus solely on the concept of Total Capital—the aggregate buffer available to absorb losses before liability holders are exposed.

Amount of Capital → Once a bank has risk-weighted its assets (and subject to the regulatory taxonomy of what qualifies as capital) supervisors impose minimum ratios that must be held against those risk-weighted assets. Under Pillar I, the canonical thresholds are:

- Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1): 4.5% of RWAs

- Tier 1: 6.0% of RWAs (this includes CET1 capital)

- Total Capital: 8.0% of RWAs (this includes CET1 and Tier 1 capital)

Basel III then layers on additional, situation-specific buffers:

- Capital Conservation Buffer (CCB): +2.5% to CET1

- Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCyB): 0–2.5%, depending on macro conditions

- G-SIB Surcharge: 1–3.5% for systemically important banks

In practice, this means large banks must operate with 7–12%+ CET1 and 10–15%+ Total Capital under normal Pillar I conditions. But regulators do not stop at Pillar I. They impose stress-testing regimes and, where warranted, additional capital add-ons—what they call Pillar II. As a result, effective capital requirements can easily rise well above 15%. You want to know more about a bank’s balance sheet composition, risk management practices, and amount of capital held? Look at their Pillar III—not a joke.

As a reference point, 2024 data show global G-SIBs operating with an average CET1 ratio of roughly 14.5%, and Total Capital ratios around 17.5–18.5% of RWAs.

Tether: an Unregulated Bank

We can now see why the debate around whether Tether is good, bad, solvent, insolvent, FUD, fraud, or anything else misses the point. The real question is simpler and more structural: does Tether hold enough Total Capital to absorb the volatility of its asset profile?

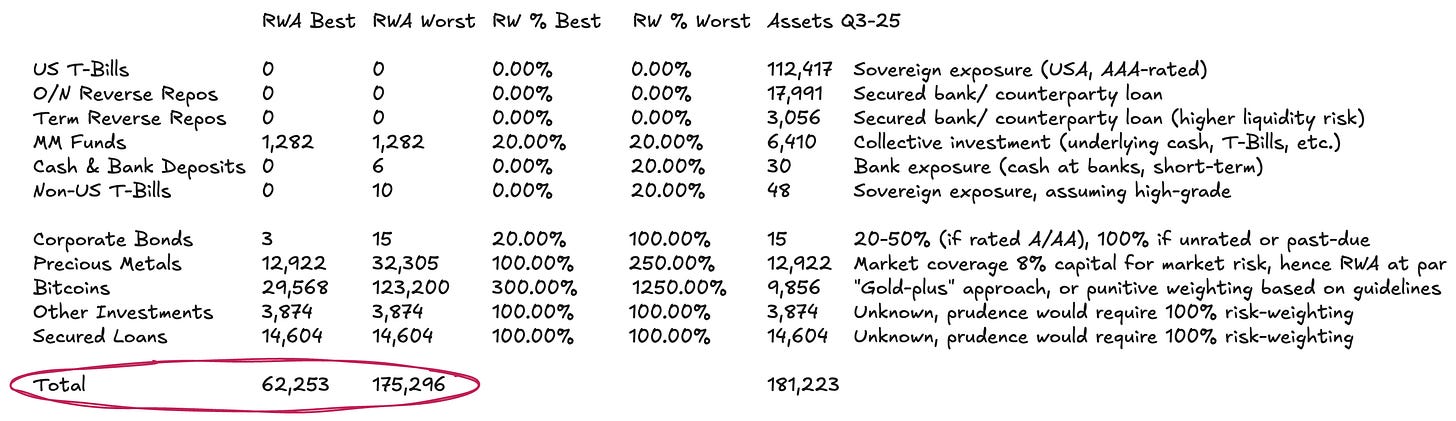

Tether does not publish a Pillar III report (for reference, here is UniCredit’s); instead, it offers a thin reserve report—here is the latest. The information is minimal by Basel standards, but still sufficient to attempt a rough calculation of Tether’s risk-weighted assets.

Tether’s balance sheet is relatively simple:

- c. 77% in money-market instruments and other USD-denominated cash equivalents—these attract minimal or zero risk-weighting under the Standardized Approach

- c. 13% in physical and digital commodities

- The remainder in loans and miscellaneous investments that cannot be meaningfully assessed from the disclosures

Risk-weighting categories (2) requires nuance. Under standard Basel guidance, $BTC carries a punitive 1,250% risk-weight. With an 8% Total Capital requirement applied to RWAs—see above, this effectively means regulators demand full reserving for $BTC—a 1-for-1 capital charge that assumes zero loss-absorption capacity. We include this in our worst-case scenario, though it is clearly anachronistic—especially for an issuer whose liabilities circulate in crypto markets. We think $BTC should be treated more coherently as a digital commodity. There is a clear framework and a common practice for the treatment of physical commodities such as gold—of which Tether holds a substantial amount: when directly custodied (as is the case for portions of Tether’s gold and surely for $BTC) there is no inherent credit or counterparty risk. The risk is purely market risk, since liabilities are denominated in USD rather than in the commodity. Banks typically hold 8–20% capital against gold positions to buffer price volatility—translating into 100-250% risk-weighting. A similar logic could apply to $BTC, adjusted for its very different volatility profile. Since BTC has exhibited 45–70% annualized volatility post-ETF approval—compared with 12–15% for gold—a simple baseline would be to scale the risk-weight by roughly 3× relative to gold.

For category (3), the loan book is entirely opaque. With no visibility into obligors, maturities, or collateral, the only defensible option is to apply a 100% risk weight. This is still generous, given the absence of any credit information.

Putting these assumptions together, for total assets of roughly $181.2bn, Tether’s RWAs fall in a range between c. $62.3b and c. $175.3b, depending on how one treats the commodity portfolio.

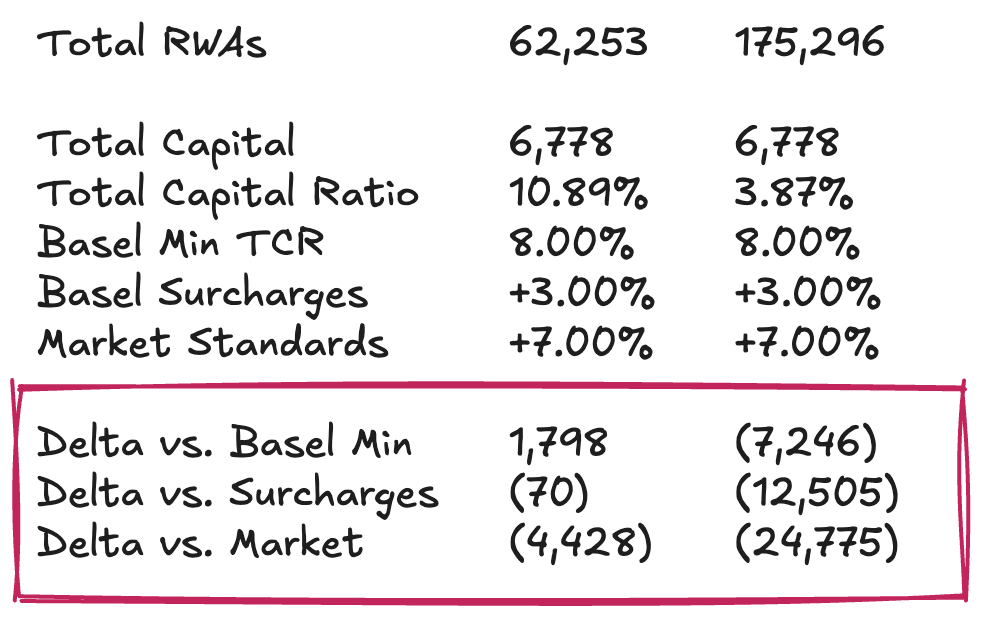

Tether’s Capital Position

We can now add the last piece and look at Tether’s equity, or excess reserves, not in absolute terms, but relative to its RWAs. In other words: what is Tether’s Total Capital Ratio—TCR, and how does it compare to regulatory minima and market practice? This is where the exercise becomes more opinionated. For this reason, my aim is not to deliver a definitive verdict on whether Tether has enough capital to comfort $USDT holders, but rather to offer a framework that allowing the audience to break the question into digestible parts and form an assessment in the absence of any formal prudential regime.

Assuming excess reserves of around $6.8b, Tether’s Total Capital Ratio would range between 10.89% and 3.87%, depending largely on how we choose to treat its $BTC exposure and how conservative we want to be about price volatility. Full reserving of $BTC, while consistent with Basel’s most punitive reading, looks excessive to me. A more reasonable base case assumes a capital buffer sufficient to withstand a 30-50% $BTC price move, which is well within observed history.

Under that base case, Tether screens as reasonably collateralized against what a minimal regulatory setup would demand. Against market benchmarks, however (think large, well-capitalized banks) the picture is less flattering. On those standards, Tether would need roughly $4.5b of additional capital to sustain the current $USDT issuance. The harsher, fully punitive $BTC treatment implies instead capital shortfalls in the $12.5–25b range, which I consider disproportionate and ultimately not fit for purpose.

Standalone vs. Group → Tether’s standard counter-argument on collateralization is that, at the Group level, it is sitting on a very large cushion of retained earnings. And the numbers are non-trivial: by the end of 2024, Tether reported yearly net profits above $13b and Group equity surpassing $20b. More recently, the Q3 2025 attestation points to $10b+ year-to-date profit. The counter-counter-argument, however, is that none of this could be considered regulatory capital in the strict sense for $USDT holders. These retained profits (on the liabilities side) and proprietary investments (on the assets side) sit at Group level, outside the ring-fenced reserve perimeter, and Tether has the power but not the obligation to downstream them into the issuing entities if something goes wrong. Liability segregation seems to be precisely what gives management the option to recapitalize the token business—but not a hard commitment to do so. To treat the Group’s retained earnings as if they were fully available loss-absorbing capital for $USDT is therefore optimistic. A serious assessment would need to look at the Group balance sheet itself, including positions in renewable-energy projects, bitcoin mining, AI and data infrastructure, P2P telecoms, education, land and stakes in gold-mining and royalty companies. The fair value of that equity cushion depends on the performance and liquidity of these risk assets—and on Tether’s willingness, in a crisis, to sacrifice them to make token holders whole.

If you were expecting a definitive answer, I’m afraid you’ll be disappointed. But that is broadly how Dirt Roads works. The journey is the prize.

Disclaimer:

- This article is reprinted from [Dirt Roads]. All copyrights belong to the original author [Luca Prosperi]. If there are objections to this reprint, please contact the Gate Learn team, and they will handle it promptly.

- Liability Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not constitute any investment advice.

- Translations of the article into other languages are done by the Gate Learn team. Unless mentioned, copying, distributing, or plagiarizing the translated articles is prohibited.

Related Articles

The Future of Cross-Chain Bridges: Full-Chain Interoperability Becomes Inevitable, Liquidity Bridges Will Decline

Solana Need L2s And Appchains?

Sui: How are users leveraging its speed, security, & scalability?

Navigating the Zero Knowledge Landscape

What is Tronscan and How Can You Use it in 2025?